Movie Review - The Stendhal Syndrome

- Details

- Category: Movie & TV Reviews

- Published on Monday, 01 May 2017 20:27

- Written by Administrator

- Hits: 1447

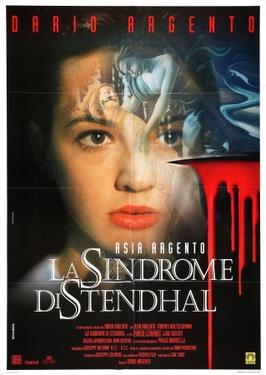

The Stendhal Syndrome

1996

dir Dario Argento

In Italian director Dario Argento's 1996 horror-thriller The Stendhal Syndrome, his own daughter Asia Argento stars as Anna Manni, a detective investigating a series of brutal sex killings in Rome and Florence. So begins perhaps the most awkward take-your-daughter-to-work day in cinema history.

Manni suffers from the eponymous Stendhal Syndrome, a real life disorder whose victims suffer seizures and hallucinations when exposed to art. As the investigation unfolds, Anna and the killer play a game of cat-and-mouse-who-gets-raped-a-lot. Fascinated by Anna, the killer sets traps for her, pontificating about the power of art and the intensity of the creative experience between bouts of puttin' his lotion in her basket. After enduring a grueling assault in an abandoned tunnel, complete with demonic hallucinatory Stendhal graffiti, Anna finally manages to draw her gun and put him out of her misery.

After killing the perp, Manni experiences post-traumatic stress. She transforms her appearance and personality and imagines taunting phone calls from the dead killer. The plot thickens as copycat killings of people close to Manni suggest that she may not be hallucinating.

Taken at face value, The Stendhal Syndrome is a not-too-shabby killer thriller with obvious influences from Alfred Hitchcock and Brian DePalma as well as Argento's own signature Italian travelogue cinematography. Like William Friedkin, Dario Argento excels at infusing his films with a sense of place that is at once authentic and otherworldly and The Stendhal Syndrome, with its dreamlike artistic landscapes and haunting Ennio Morricone soundtrack, is no exception. The opening sequence, for example, where Manni takes in the view of the Ponte Veccio from the Uffizi Gallery before falling into Brueghel's Landscape with the Fall of Icarus leaves little doubt that in this film one does not simply walk into Florence. And while a few of the effects, such as the bullet's point of view as it travels through a body and the pill's point of view as it travels down the esophagus, are somewhat dated and awkward, others are quite stunning and imaginative.

But for a film that features such visceral sexual violence, it is not enough to be merely not-too-shabby. There is a fine line between using sexualized violence in entertainment and rapesploitation. The Stendhal Syndrome toes that line with refreshing deftness. Just as Hitchcock used the lurid violence of Psycho's shower scene to bury the complexity of Norman Bates' mommy issues, so does Argento use sexual violence here to misdirect us from the true villain of his piece, art itself. And just as the victims of assault can find themselves identifying with their assailants, Manni moves from art to artifice as she struggles to process her traumatic experience with her all-too-real attacker. The Stendhal Syndrome is ultimately about the transformative power of art, over us individually and as a culture. Art is presented here as a filter, a prism through which the light of reality is split and refracted, a vehicle for translating abstract myth into immediate experience. But Manni is incapable of processing art. For her, art is not a means to explore reality. Rather it is a perverse substitute for reality itself. Art is an assailant that imprisons her spirit rather than elevating it.

The uniquely Italian, uniquely Argento, rendition of this power makes The Stendhal Syndrome more than a mere shockfest. The horror of the film hangs literally on the walls, its sadism so ubiquitous that any response to it is bound to be disordered. But this is no contrived Night Gallery of cheap knock offs. It is our authentic legacy, note for bloody note.

On a recent trip to Rome, I had the opportunity to take the Vatican Museum tour. It's a fascinating multi-hour death march as you are squeezed by the crowd through the toothpaste tube of western history. The tour begins in the classical period, with busts of Roman and Greek gods, politicians, artists and other bustworthy subjects, and then literally turns left into the Renaissance and modern periods, where it becomes Golgothapalooza. One can almost hear Life of Brian's Michael Palin crooning on the audio tour "and here we have...crucifixion?...good...moving on we see...crucifixion?...good...now if you'll follow the yellow line into the Crucifixion Room, we'll see some renderings of the...crucifixion?...good..."

Perhaps if artists throughout the centuries had expended as much oil and canvas on the Sermon on the Mount as they did on the crucifixion, The Last Temptation of Christ would have been a bigger hit and The Passion of the Christ would be relegated to midnight triple features alongside Saw and Hostel, where it belongs.

At least there was a moral point to Saw.

-Jason Shankel

July, 2011